The Thirties, Forties, and Fifties

By the early 1930s, the work which Mr. Robinson envisioned a decade earlier was clearly resulting in better lives for families surrounding the Station. Louis Hillenmeyer of Lexington, who had been appointed by the UK Board of Trustees to evaluate the progress of the substation, reported that “so much has been done in the limited amount of time that the Station has been in operation I feel that its usefulness is firmly established.” He went on to praise the employees of the Station for their diligence in their work.

Forestry work in the early years of the Station involved observation studies of the regrowth of yellow poplar, a species of good value because it was widely used in building and flooring, and studies of an imported species, Japanese Red Pine, an Asian species of pine noted for its strength and durability as a wood and also as a traditional plant used in bonsai arboriculture.

From the onset of negotiations for the gift to the University of Kentucky, Dean Cooper was concerned about the mineral rights on the properties. The mineral rights had not been transferred to the University, but rather had been sold by Robinson and Mowbray to W.E. Chilton of Charleston, West Virginia, taking mortgage notes in payment. Cooper was concerned that the possibility existed that Chilton either would explore the properties for coal or would transfer the mineral rights to someone who would, and that exploration could disturb the Station’s reforestation efforts.

As it turned out, Chilton failed to pay some of his promissory notes and the taxes on the mineral rights. After a futile attempt at forcing the sale of the mineral rights to the University of Kentucky for non-payment of taxes, Robinson foreclosed the mortgage and regained the coal rights, which he and his wife conveyed to the University of Kentucky in late 1930. Gas and oil rights, however, were not transferred to the University.

The 1930s brought with them both hardship and opportunities. Wages for logging at the forest, which had been $2 per day in the late 1920s, were reduced to $1 and $1.50 per day due to the depression gripping the world. Fire wardens were paid $5 per month to watch for fires during spring and fall fire seasons. A blight invaded the forest with a vengeance and virtually killed every native American chestnut tree standing. (Chestnuts comprised a substantial portion of the forest.) Early tasks were primarily building fire roads, removing fire hazards, fighting fires, and building low water bridges.

Early reports from Superintendent Jones to Dean Cooper highlight the activities at the Station and forest in curious detail, including lists of the number of fires, fire dates, acres burned, location, damage estimates, labor costs for fighting fires, and the like. From those reports, it appears that a great deal of activity was centered on removing and converting to lumber the dead chestnuts that had been killed by the blight.

Those early reports indicate that telephone service to Robinson Forest headquarters was completed in 1932 by installing a line from old Highway 15 to the headquarters, a distance of 6.5 miles, at a cost of $597. And a horse named “Joe” that had been lent to the home demonstration agent during the winter of 1934-1935 was returned to Robinson Forest. He was sold in 1937 for $75, which was only $5 less than what was paid for him a few years earlier.

Depression-era federal programs, notably the Civilian Conservation Corps, did help the forest with facilities. A CCC camp was established and opened in 1933 on Buckhorn Fork, part of the Forest. Those working with the program cleared trails, built fire breaks, planted trees, cleared more than 70 miles of foot trails in the forest, constructed three fire towers (including the 99 foot steel tower on Boarding House Knob, still in use today) and worked with the resident forester to improve stands. The CCC camp was closed in 1936 and the buildings and area were allocated to the University’s engineering college, which used the facilities to train students in civil engineering techniques until the middle 1950s.

The National Youth Administration, which was set up in the mid 1930s as part of the Emergency Relief Appropriations Act to provide work training for unemployed youth and part-time employment for needy students, started building a camp at the forest in 1939. Five rustic buildings were constructed from blight-killed chestnut. The buildings were only partially completed when work stopped in 1941 as a result of the start of World War II. (All materials and hardware remained in storage until 1954; when the buildings were completed they were used by the university for summer camps in 1956.)

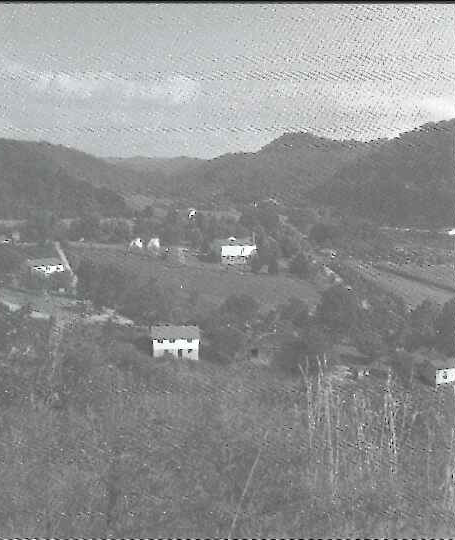

From the inception of the University’s ownership of the forest through the 1950s, the bottoms were farmed. Vegetable gardens and fruit orchards were established for the families living in the forest. Other crops, including field corn, soybeans, alfalfa, lespedeza, orchard grass, and oat hay were raised to feed the horses and mules essential to the forest operation.

In 1943, foresters at the forest planted stands of Asiatic Chestnuts, often called Chinese Chestnuts, to see how well they grew in the mountain soils. (Recall, that the American Chestnuts had all but disappeared from the forest due to blight in the previous decades.)

In 1947, a cooperative agreement between the University of Kentucky and the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife established major portions of Clemons Fork, Robinson Fork, and Coles Fork as a game refuge. Deer, beaver, turkey, and ruffed grouse were released; the beavers disappeared quickly but the remaining species thrived and continue to be abundant in the forest. In 1954, the university purchased an American No. 1 sawmill to be used for research and demonstration at the forest. Within six months of its operation, the sawmill had processed about 65,000 board feet of lumber.

In 1957, an International TD-14 tractor with a blade, winch, and logging arch was purchased to help with logging in the forest. Until this time, all work in the forest was completed with the aid of mules and horses. The following year, the university purchased two pieces of secondary wood manufacturing equipment: an Oliver double arbor universal saw and a 36-inch band saw. The present sawmill was put into operation in 1963. An herbicide (2,4,5T) was first used for timber stand improvement in 1959 at total cost including labor of $5.40 per acre.

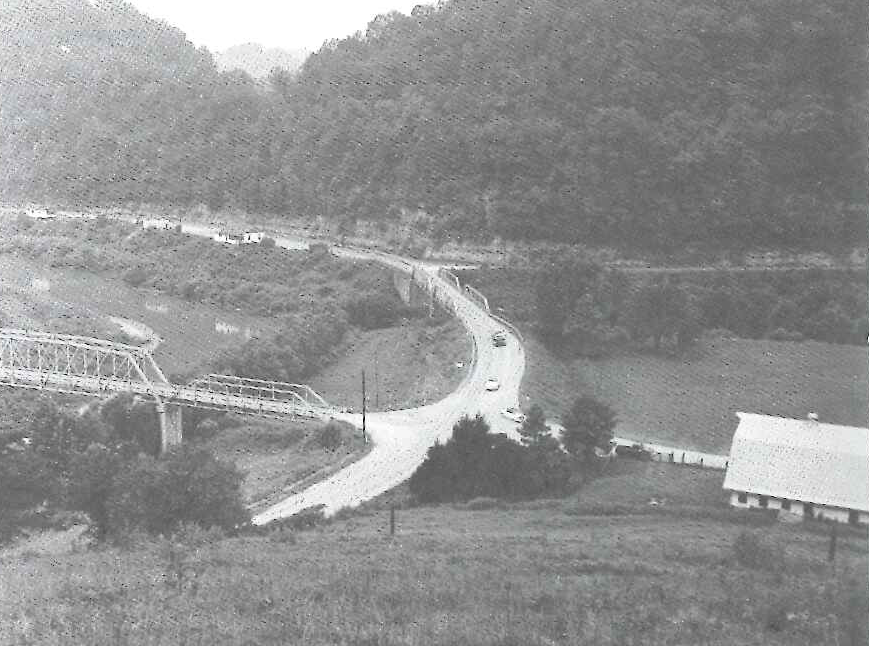

Beginning apparently in the early 1940s, 4-H camps were held every June at the Robinson Station under the supervision of Mr. J.M. Feltner and later Mr. Boyd Wheeler. These camps were an annual event through the 1950s, except for the summer of 1950, when the bridge to the Station was closed to all but foot traffic. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad depot was used as the 4-H kitchen at first, but the depot was razed in 1948.

Robinson Auditorium at the Station was constructed in 1940 and 1941 by the Works Progress Administration, using wood from the forest. The auditorium was used as a community center, as well as for Station activities. Annual family reunions, class reunions, weddings, and many other community meetings and activities were held at the auditorium. The building also was used as a dorm and kitchen for the first nine years of the Wood Technician School, which began at the forest in 1962 and operated until 1982. While it is no longer rented to outside groups, the auditorium continues to be used for Quicksand Extension area activities.

The Station road’s maintenance, heretofore a responsibility of the College of Agriculture, was turned over to the Kentucky Highway Department in 1950; and the state painted and repaired the old bridge that had been closed to all but foot traffic for several months because of its unworthiness to carry heavy cars and trucks. The roads into the Station were blacktopped in 1952.

It was also in the early 1950s that W.D. “Army” Armstrong, a horticulturist headquartered at the other end of the state at the West Kentucky Experiment Station in Princeton, became involved in expanding horticulture research at Quicksand. In 1952, he began research on dwarf apples, pecans, grapes, blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries. In addition, agronomists began experimental plots to evaluate hybrid corn varieties. In 1950, about 30 different hybrid corn varieties were tested at the Station. To this day, new corn varieties are subjected to testing at the Quicksand Station and results published each year.

The dairy herd, first established at the Station in the 1920s, was terminated in 1957 and a sheep unit was established. The swine and poultry units began to be phased out at this time as well.

A stream of research on horticultural crops was initiated in 1957 and still continues. The first plastic greenhouse, an innovation in the field in the 1950s, was erected in the spring of 1957 to test whether it could perform as well as conventional glass greenhouses. A second one was added in the fall of that year. Later, two more were built to evaluate the efficiency of various fuel types. These early greenhouses were razed in the mid 1970s, and another has replaced them, built in 2001.

Major Jones, the superintendent of the Station from its inception, retired in 1957 and Charles Derrickson became the Station’s superintendent. (Derrickson remained in the position until 1965.)